Wittgenstein’s hut (restored) in Skjolden, Norway

Wittgenstein’s hut (restored) in Skjolden, Norway

Wittgenstein is frequently characterized as detached and analytical. Yet his most significant contributions possessed deeply spiritual dimensions.

Scholar Martin Pilch (2016) observed that Wittgenstein employed extended em dashes as typographical expressions of reverence, often doubling them——like this. It was, Pilch suggests, “a kind of typographical form of prayer.”

During winter 1914-15, stationed in Kraków, Wittgenstein struggled creatively. His intellectual energies felt depleted (müde).

“It is as if a flame has been extinguished and I must wait till it begins to burn again of its own accord.”

He pursued the redeeming word (das erlösende Wort)—a transformative concept that would restore clarity to his blocked thinking.

On September 1, 1914, Wittgenstein’s regiment briefly stopped in Tarnów, Poland. He discovered Tolstoy’s 1892 Gospel in Brief in a local bookshop.

Subsequently, he declared this encounter life-changing.

“You can’t hear God speak to someone else, you can hear him only if you are being addressed.”

Scholar Marjorie Perloff (2022) contends that wartime experiences taught Wittgenstein that no singular redemptive concept exists—only perpetual inquiry. This interpretation warrants consideration, though alternative readings merit exploration.

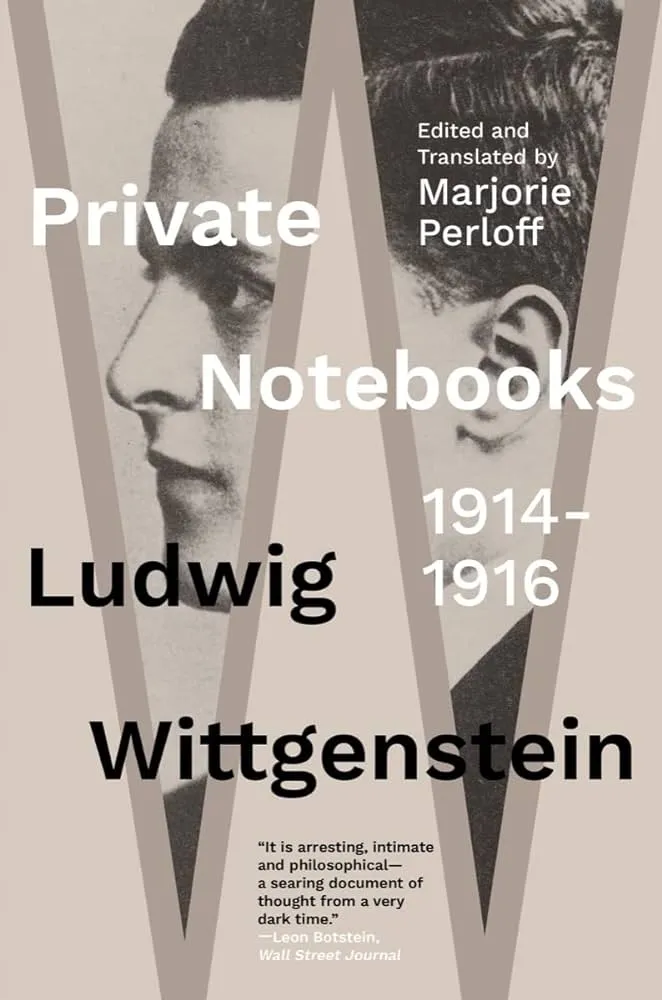

Wittgenstein’s Private Notebooks 1914-1916

Wittgenstein’s Private Notebooks 1914-1916

Perhaps no keystone concept unlocks everything, yet this doesn’t necessarily mean absence of transcendent meaning. Characterizing the situation as containing only questions and no answers oversimplifies matters.

The relentless pursuit toward precision and truthfulness, continually grappling with reality’s unexpected dimensions, constitutes an answer itself. Through linguistic discipline, seekers access something larger, achieving redemption—mysteriously yet verifiably. While mechanisms remain obscure, empirical observation suggests this pattern persists reliably.

Perloff’s analysis demonstrates how Wittgenstein’s celebrated analytical statement originated in earlier spiritual reflections. His most quoted line from the Tractatus reads: “Of what one cannot speak, of that one must be silent.” Yet wartime notebooks contain an earlier formulation: “To believe in a God means to see that the facts of the world are not the end of the matter,” followed by “But the connection will have been made! What cannot be said, cannot be said!”